One of my favorite New Yorker cartoons shows a government official handing a document to a subordinate. The caption reads, “Good stuff, Chip. Now, smarten up and dumb it down.”

The laugh comes from our understanding that people can only absorb so much complex information, and thus prefer to have things boiled down to digestible nuggets – even if important details are lost in that process.

This has too often happened with financial advice over the past couple of decades. Knowing that many people are afraid to invest for fear they “don’t know enough,” the financial industry has offered a simple solution – passive investing. While this can be a solid investment strategy, it may not be the best approach, especially for investors with limited risk tolerance.

Passive investing, by strict definition, entails owning the market or a broad market index fund and never trading. As a reminder, you can’t own an index, only a fund that attempts to track an index. Active investing is by nature anything besides a pure “buy and hold” strategy of a particular index fund.

In reality, there is no such thing as pure passive investing, just various shades of active investing. If an investor chooses to hold the S&P 500 index fund, widely regarded as a passive strategy, that investor is actively choosing to hold only U.S. stocks. This is an active decision to only invest in about 10% of the world’s more than $240 trillion investable marketplace, which includes U.S. small- and mid-cap stocks, the U.S. bond market, and international markets. Similarly, any approach that uses multiple passive vehicles (such as index funds and ETFs) is, by nature, an active strategy.

The Active Vs. Passive Debate

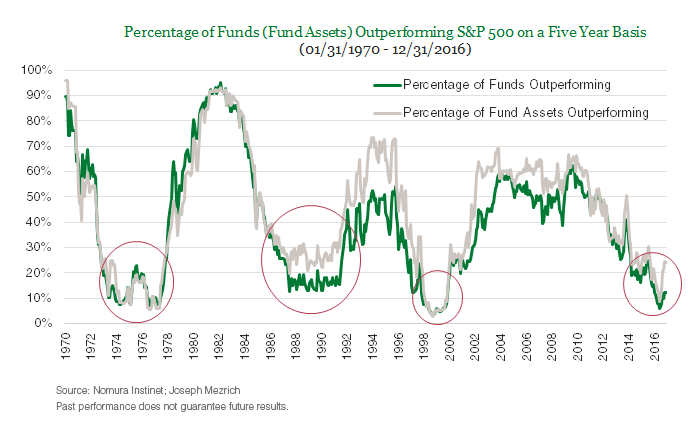

So let’s discuss the comparative performance of passive-ish strategies versus more active approaches. In short, which do better? Do the vast majority of active funds underperform their index fund counterparts?

The real answer is that some do and some don’t. But it’s not nearly as one-sided as some recent headlines would have you believe. A Standard & Poor’s study highlighted in The Wall Street Journal claims that more than 90% of actively managed large-cap equity funds underperformed their index over the past 15 years.

But on the other end of the spectrum, a recent PIMCO/Morningstar study shows that the majority of active bond funds and bond ETFs do in fact beat their index fund counterparts. According to PIMCO, “Taking the three largest categories within fixed income for the same 5-year period, 84%, 81% and 60% of active funds and ETFs outperformed their median passive peers in intermediate-term, high yield and short-term categories.”

The study goes on to show that stock (or equity) mutual funds don’t fare quite as well against their passive competition; but about one-third of active stock funds do best their passive competition on a one-, three-, five-, seven- and 10-year basis. These data stand in contrast to the Standard & Poor’s study, mostly due to how each study categorizes funds that are no longer in existence.

What accounts for the stark difference between the payoffs of active bond versus active equity strategies? The unique nature of the bond market. Unlike stocks, bonds mature after a number of years, resulting in more turnover in the bond market. To illustrate, new securities make up only about 1% in equity markets annually, rivaled by a healthy 20% for bond market capitalization. Additionally, bonds are often offered at price points aimed at driving demand. But for passive managers buying new securities only when they join an index, they miss out on the revolving concessional pricing.

So, in reality, both active and passive investment vehicles have significant merit. Notice I said vehicles. But there’s a distinction to be made between investment vehicles, and how overall investment strategy or approach is defined. This brings me back to my earlier point.

There Really Is No Such Thing As Pure Passive Investing, Just Various Shades Of Active Investing.

Why? Human nature. We are creatures of emotion.

The basic emotions of fear and greed are the real drivers behind how most people manage their portfolios. These are primal feelings, and they influence investors more than sometimes meets the eye. We all have similar feelings about our money: it’s hard earned; we hate to lose it, we want to keep it safe, but we also have a desire for it to earn and grow.

When fear creeps in, people are vulnerable to knee-jerk reactions to market fluctuations.

Empirical data from Dalbar shows that the majority of individual investors have little tolerance for dramatic market moves, which leads to ill-timed buying and selling, otherwise known as poor “market timing.”

Say our index fund goes down when the market dips due to a poor jobs report. We see ourselves losing money on paper. The natural reaction is to want to do something to minimize any additional loss. It goes back to money being hard earned – we don’t want to let any of it slip away. But selling out too soon could be a costly move.

Greed can get the best of us, too. We all want our investments to do well, and it can be frustrating to feel like everyone else is running a faster or better race. If most folks are having a 12% year, and you’re having a 2% year, it’s natural for a sense of frustration to set in. “Why am I not earning 12% as well?” But investors must ask themselves two questions. Is what everyone else is doing realistic for me? Are the risks involved worth it for me?

Rarely have I met an investor who has just ridden out the full ups and downs of owning one index fund through an entire market cycle; the emotional reality of this approach is almost always too much to bear.

Statistics show that most people understand their limits when it comes to money management. Only about 25% of investors like to handle their investments completely on their own. These folks believe in their ability to fight the financial and emotional ups and downs that confront all investors each and every day. The remaining 75% of investors admit they don’t have the time, energy, or inclination to go it alone. They want some help.

Working With A Financial Advisor Can Be A Good Way To Insulate A Portfolio From The Whipsaw Of Emotion.

A good advisor works to understand a client’s goals and risk tolerance. He then helps the investor manage the math and science behind his portfolio, and also help coach and educate in an attempt to stabilize the dramatic emotions that come with investing. A good financial advisor can talk investors though those palpable moments of fear and greed. They help clients make rational rather than emotional investment decisions.

Advisors can also ease a client’s mind by creating a well-defined strategy, using diversification, and asset allocation. When a portfolio is allocated in a truly diversified way, those 10%, 20%, or 50% stock market moves will elicit less fear or greed. Diversification dampens blows to both our financial and emotional well-being.

And it provides a key element to investment health – participation. Investors have to participate in markets over time in order to experience growth. And they must, to some extent, actively participate in managing their own money.

Partnering with the right advisor can result in a notable improvement in return. Based on extensive research, Vanguard, one of the world’s largest investment companies, has found a quantifiable increase in return when an investor works with a financial advisor. Vanguard calls this advantage the Advisor’s Alpha. When certain best practices are followed, the result can be an Alpha in the 3% per year range.

So, Is The Purely Passive “Buy And Hold” Approach Best For Investors?

The answer is, unlikely. Especially if you are a human with any sort of emotion. Long term index fund returns typically boast significant returns but come with dramatic peaks and valleys that throw investors off track. Instead, most investors are better suited to employ a broad array of low-cost index funds, low-cost active funds, and ETFs that cover several different investment categories, while considering their individual tolerance for risk.

This creates a balanced portfolio somewhere on the passive-active continuum. And when we use any mix of passive funds to accomplish a balanced portfolio, we have entered the realm of active investing. And for most of us, it’s the right place to be.